Trump’s White Nationalists

While the election of Obama led some to believe that racism had been exorcized, the triumph of Trump caused speculation that the demon had merely retreated to the shadows of the internet. In August of 2017, the city of Charlottesville, VA served as the location of a “United the Right” march. This march, which seems to have been a blend of neo-Nazis, white-supremacists and other of the alt-right, erupted in violence. One woman who was engaged in a counter-protest against the alt-right, Heather Heyer, was murdered. Officers Cullen and Bates were also killed when their helicopter crashed, although this appears to have been an accident.

While Trump strikes like an enraged wolverine against slights real or imaginary against himself, his initial reply to the events in Charlottesville were tepid. As has been his habit, Trump initially resisted being critical of white supremacists and garnered positive remarks from the alt-right for their perception that he has created a safe space for their racism. This weak response has, as would be expected, been the target of criticism from both the left and the more mainstream right.

Since the Second World War, condemning Nazis and Neo-Nazis has been extremely easy and safe for American politicians. Perhaps the only thing easier is endorsing apple pie. Denouncing white supremacists can be more difficult, but since the 1970s this has also been an easy move, on par with expressing a positive view of puppies in terms of the level of difficulty. This leads to the question of why Trump and the Whitehouse responded with “We condemn in the strongest possible terms this egregious display of hatred, bigotry and violence on many sides, on many sides” rather than explicitly condemning the alt-right. After all, Trump pushes hard to identify acts of terror by Muslims as Islamic terror and accepts the idea that this sort of identification is critical to fighting such terror. Consistency would seem to require that Trump identify terror committed by the alt-right as “alt-right terror”, “white-supremacist terror”, “neo-Nazi terror” or whatever would be appropriate. Trump, as noted above, delayed making specific remarks about white supremacists.

Some have speculated that Trump is a racist. Trump denies this, pointing to the fact that his beloved daughter married a Jew and converted to Judaism. While Trump does certainly make racist remarks, it is not clear if he embraces an ideology of racism or any ideology at all beyond egoism and self-interest. While the question of whether he is a racist is certainly important, there is no need to speculate on the matter when addressing his response (or lack of response). What matters is that the weakness of his initial response and his delay in making a stronger response sends a clear message to the alt-right that Trump is on their side, or at least is very tolerant of their behavior. It could be claimed that the alt-right is like a deluded suitor who thinks someone is really into them when they are not, but this seems implausible. After all, Trump is very easy on the alt-right and must be pushed, reluctantly, into being critical. If he truly condemned them, he would have reacted as he always does against things he does not like: immediately, angrily, repeatedly and incoherently. Trump, by not doing this, sends a clear message and allows the alt-right to believe that Trump does not really mean it when he condemns them days after the fact. As such, while Trump might not be a racist, he does create a safe space for racists. As Charlottesville and other incidents show, the alt-right presents a more serious threat to American lives than does terror perpetrated by Muslims. As such, Trump is not only abetting the evil of racism, he could be regarded as an accessory to murder.

It could be countered that Trump did condemn the bigotry, violence and hatred and thus his critics are in error. One easy and obvious reply is that although Trump did say he condemns these things, his condemnation was not directed at the perpetrators of the violence. After seeming to be on the right track towards condemning the wrongdoers, Trump engaged in a Trump detour by condemning the bigotry and such “on many sides.” This could, of course, be explained away: perhaps Trump lost his train of thought, perhaps Trump had no idea what was going on and decided to try to cover his ignorance, or perhaps Trump was just being Trump. While these explanations are tempting, it is also worth considering that Trump was using the classic rhetorical tactic of false equivalence—treating things that are not equal as being equal. In the case at hand, Trump can be seen as regarding those opposing the alt-right as being just as bigoted, hateful and violent as the alt-right’s worst members. While there are hateful bigots who want to do violence to whites, the real and significant threat is not from those who oppose the alt-right, but from the alt-right. After all, the foundation of the alt-right is bigotry and hatred. Hating Neo-Nazis and white supremacists is the morally correct response and does not make one equivalent or even close to being the same as them.

One problem with Trump’s false equivalence is that it helps feed the narrative that those who actively oppose the alt-right are bad people—evil social justice warriors and wicked special snowflakes. This encourages people who do not agree with the alt-right but do not like the left to focus on criticizing the left rather than the alt-right. However, opposing the alt-right is the right thing to do. Another problem with Trump’s false equivalence is that it encourages the alt-right by allowing them to see such remarks as condemning their opponents—they can tell themselves that Trump does not really want to condemn his alt-right base but must be a little critical because of politics. While Trump might merely be pragmatically appealing to his base and selfishly serving his ego, his tolerance for the alt-right is damaging to the country and will certainly contribute to more murders.

Guarding the Trumps

Embed from Getty Images

While it has not always been the case, the current practice is for the American taxpayer to foot the bill for extensive protection of the president and their family. When Bush was president, there were complaints from the left about the costs incurred protecting him when he went to his ranch. When Obama was president, the right criticized him for the cost of his vacations and trips. Not surprisingly, Trump was extremely critical of the expenses incurred by Obama and claimed that if he were president he would rarely leave the White House. Since Trump is now president, it can be seen if he is living in accord with his avowed principles regarding incurring costs and leaving the White House.

While Trump has only been president for roughly a month, he has already made three weekend trips to his Mar-a-Lago club since the inauguration. While the exact figures are not available, the best analysis places the cost at about $10 million for the three trips. In addition to the direct cost to taxpayers, a visit from Trump imposes heavy costs on Palm Beach Country which are estimated to be tens of thousands of dollars each day.

Trump’s visit also has an unfortunate spillover cost to the Lantana Airport which is located six miles from Mar-a-Lago. When Trump visits, the Secret Service shuts down the airport. Since the airport is the location of twenty businesses, the shut down costs these businesses thousands of dollars. For example, a banner-flying business claims to have lost $40,000 in contracts to date. As another example, a helicopter company is moving its location in response to the closures. The closures also impact the employees and the surrounding community.

Since Trump also regularly visits Trump tower and his wife and youngest son live there, the public is forced to pay for security. The high-end estimate of the cost is $500,000 per day, but it is probably less—especially when it is just Melania and her son staying there. It must be noted that it cost Chicago about $2.2 million to protect Obama’s house from election day until inauguration day. However, Obama and his family took up residence in the White House and thus did not require the sort of ongoing protection of multiple locations that Trump now expects.

The rest of Trump’s family also enjoys security at the taxpayers’ expense—when Eric Trump took a business trip to Uruguay it cost the country about $100,000 in hotel room bills. Given that such trips might prove common for Trump’s family members, ongoing expenses can be expected.

The easy an obvious reply to these concerns is that the protection of the president and their family is established policy. Just as Bush and Obama enjoyed expensive and extensive protection, Trump should also enjoy that protection as a matter of consistent policy. As such, there is nothing especially problematic with what Trump is doing. Trump himself also contends that while he attacked Obama for taking vacations, when he goes to Mar-a-Lago and New York, it is for work. For example, he met the prime minister of Japan at Mar-a-Lago for some diplomatic clubbing and not for a weekend vacation in Florida.

A reasonable counter to this reply is to point out the obvious: there is no compelling reason why Trump needs to conduct government business at Trump Tower and Mar-a-Lago. Other than the fact that Trump wants to go to these places and publicize them for his own gain, there is nothing special about them that would preclude conducting government business in the usual locations. As such, these excessive expenses are needless and unjustified.

There is also the harm being done to the communities that must bear the cost of Trump and his family and the financial harm being done to the Lantana Airport. Trump, who professes to be a great friend of the working people and business, is doing considerable harm to the businesses at the airport and doing so for no legitimate reason. This make his actions not only financially problematic, but also morally wrong—he is doing real and serious harm to citizens when there is no need to do so.

There is also an additional moral concern about what Trump is doing, namely that his business benefits from what he is doing. Both the Defense Department and Secret Service apparently plan on renting space in Trump Tower, thus enabling Trump to directly profit from being president. If the allegedly financially conservative Republicans were truly concerned about wasting taxpayer money, they would refuse this funding and force Trump to follow the practices of his predecessors. Or, if Trump insists on staying at Trump tower, the government should require that he pay all the costs himself. After all, being at Trump Tower benefits him and not the American people. Trump also gains considerable free publicity and advertising by conducting state business at his own business locations. He can, of course, deny that this is his intent—despite all the evidence to the contrary.

Just as the conservative critics of Obama were right to keep a critical eye on his travel expenses, they should do the same for Trump. While Trump can, as noted above, make the case that he is at least doing some work while he is at Trump tower and Mar-a-Lago, there is the reasonable concern that Trump is incurring needless expenses and doing significant harm to the finances of the local communities and businesses. After all, there is no reason Trump needs to work at his tower or club. As such, Trump should not take these needless and harmful trips and the fiscal conservatives should be leading the call to reign in this waster of public money and enemy of small businesses.

Is Trump’s Presidency Legitimate?

Representative John Lewis, a man who was nearly killed fighting for civil rights, has claimed that Trump is not a legitimate president. While some dismiss this as mere sour grapes, it is certainly an interesting claim and one worth given some consideration.

The easy and obvious legal answer is that Trump’s presidency is legitimate: despite taking a trouncing in the popular vote, Trump won the electoral college. As such, he is the legitimate president by the rules of the system. It does not matter that Trump him denounced the electoral college as “a disaster for democracy”, what matters is the rules of the game. Since the voters have given tacit acceptance of the system by participating and not changing it, the system is legitimate and thus Trump is the legitimate president from this legal standpoint. From a purely practical standpoint, this can be regarded as the only standpoint that matters. However, there are other notions of legitimacy that are distinct from the legal acquisition of power.

In a democratic system of government, one standard of legitimacy is that the majority of the citizens vote for the leader. This can, of course, be amended to a majority vote by the citizens who bother to vote—assuming that voters are not unjustly disenfranchised and that there is not significant voter fraud or election tampering. On this ground, Hillary Clinton is the legitimate president since she received the majority of the votes. This can be countered by arguing that the majority of the citizens, as noted above, accepted the existing electoral system and hence are committed to the results. This does create an interesting debate about whether having the consent of the majority justifies the acceptance of an electoral system that can elect a president who does not win a majority of the votes. As would be suspected, people tend to think this system is just fine when their candidate wins and complain when their candidate loses. But, this is not a principled view of the matter.

Another standard of legitimacy is that the election process is free of fraud and tampering. To the degree the integrity of the electoral system is in question, the legitimacy of the elected president is in doubt. Since the 1990s the Republican party has consistently claimed that voter fraud occurs and is such a threat that it must be countered by such measures as imposing voter ID requirements. With each election, the narrative grows. What is most striking is that although Trump won the electoral college, he and his team have argued that the integrity of the election was significantly compromised. Famously, Trump tweeted that millions had voted illegally. While the mainstream media could find no evidence of this, Trump’s team has claimed that they have evidence to support Trump’s accusation.

While it seems sensible to dismiss Trump’s claims as the deranged rantings of a delicate man whose fragile ego was wounded by Hillary crushing him in the popular vote, the fact that he is now president would seem to require that his claims be taken seriously. Otherwise, it must be inferred that he is a pathological liar with no credibility who has slandered those running the election and American voters and is thus unworthy of the respect of the American people. Alternatively, his claim must be taken seriously: millions of people voted illegally in the presidential election. This entails that the election’s integrity was grossly violated and hence illegitimate. Thus, by Trump’s own claims about the election, he is not the legitimate president and the election would need to be redone with proper safeguards to keep those millions from voting illegally. So, Trump would seem to be in a dilemma: either he is lying about the election and thus unfit or he is telling the truth and is not a legitimately elected president. Either way undermines him.

It could be countered that while the Republicans allege voter fraud and that Trump claimed millions voted illegally, the election was legitimate because the fraud and illegal voting was all for Hillary and she lost. That is, the electoral system’s integrity has been violated but it did not matter because Trump won. On the one hand, this does have some appeal. To use an analogy, think of a Tour de France in which the officials allow bikers to get away with doping, but the winner is drug free. In that case, the race would be a mess, but the winner would still be legitimate—all the cheating was done by others and they won despite the cheating. On the other hand, there is the obvious concern that if such widespread fraud and illegal voting occurred, then it might well have resulted in Trump’s electoral college victory. Going back to the Tour de France analogy, if the winner claimed that the competition was doping but they were clean and still won, despite the testing system being broken, then there would be some serious doubts about their claim. After all, if the system is broken and they were competing against cheaters, then it is worth considering that their victory was the result of cheating. But, perhaps Trump has proof that all (or most) of the fraud and illegal voting was for Hillary. In this case, he should certainly have evidence showing how all this occurred and evidence sufficient to convict individual voters. As such, arrests and significant alterations to the election system should occur soon. Unless, of course, Trump and the Republicans are simply lying about voter fraud and millions of illegals voting. In which case, they need to stop using the specter of voter fraud to justify their attempts to restrict access to voting. They cannot have it both ways: either voter fraud is real and Trump is illegitimate because the system lacks integrity or the claim of significant voting fraud is a lie.

Charter Schools IV: Profit

While being a charter school is distinct from being a for-profit school, one argument in favor of charter schools is because they, unlike public schools, can operate as for-profit businesses. While some might be tempted to assume a for-profit charter school must automatically be bad, it is worth considering this argument.

As one would suspect, the arguments in favor of for-profit charter schools are essentially the same as arguments in favor of providing public money to any for-profit business. While I cannot consider all of them in this short essay, I will present and assess some of them.

One stock argument is the efficiency argument. The idea is that for-profit charter schools have a greater incentive than non-profit schools to be efficient. This is because every increase in efficiency can yield an increase in profits. For example, if a for-profit charter school can offer school lunches at a lower cost than a public school, then the school can turn that difference into a profit. In contrast. A public school has less incentive to be efficient, since there is no profit to be made.

While this argument is reasonable, it can be countered. One obvious concern is that profits can also be increased by cutting costs in ways that are detrimental to the students and employees of the school. For example, the “efficiency” of lower cost school lunches could result from providing the students with less or lower quality food. As another example, a school could not offer essential, but expensive services for students with special needs. As a final example, employee positions and pay could be reduced to detrimental levels.

Another counter is that while public schools lack the profit motive, they still need to accomplish the required tasks with limited funds. As such, they also need to be efficient. In fact, they often must be very creative with extremely limited resources (and teachers routinely spend their own money purchasing supplies for the students). For-profit charter schools must do what public schools do, but must also make a profit—as such, for-profit schools would cost the public more for the same services and thus be less cost effective.

It could be objected that for-profit schools are inherently more efficient than public schools and hence they can make a profit and do all that a public school would do, for the same money or even less. To support this, proponents of for-profit education point to various incidents of badly run public schools.

The easy and obvious reply is that such problems do not arise because the schools are public, they arise because of bad management and other problems. There are many public schools that are well run and there are many for-profit operations that are badly run. As such, merely being for-profit will not make a charter school better than a public school.

A second stock argument in favor of for-profit charter schools is based on the idea competition improves quality. While students go to public school by default, for-profit charter schools must compete for students with public schools, private schools and other charter schools. Since parents generally look for the best school for their children, the highest quality for-profit charter schools will win the competition. As such, the for-profits have an incentive that public schools lack and thus will be better schools.

One obvious concern is that for-profits can get students without being of better quality. They could do so by extensive advertising, by exploiting political connections and various other ways that have nothing to do with quality.

Another concern about making the education of children a competitive business venture is that this competition has causalities: businesses go out of business. While the local hardware store going out of business is unfortunate, having an entire school go out of business would be worse. If a for-profit school goes out of business, there would be considerable disruption to the children and to the schools that would have to accept them. There is also the usual concern that the initial competition will result in a few (or one) for-profit emerging victorious and then settling into the usual pattern of lower quality and higher costs. Think, for example, of cable/internet companies. As such, the competition argument is not as strong as some might believe.

Those who disagree with me might contend that my arguments are mere speculation and that for-profit charter schools should be given a chance. They might turn out to be everything their proponents claim they will be.

While this is a reasonable point, it can be countered by considering the examples presented by other ventures in which for-profit versions of public institutions receive public money. Since there is a school to prison pipeline, it seems relevant to consider the example of for profit prisons.

The arguments in favor of for-profit prisons were like those considered above: for-profit prisons would be more efficient and have higher quality than prisons run by the state. Not surprisingly, to make more profits, many prisons cut staff, pay very low salaries, cut important services and so on. By making incarceration even more of a business, the imprisonment of citizens was incentivized with the expected results of more people being imprisoned for longer sentences. As such, for-profit prisons turned out to be disastrous for the prisoners and the public. While schools are different from prisons, it is easy enough to see the same sort of thing play out with for-profit charter schools.

The best and most obvious analogy is, of course, to the for-profit colleges. As with prisons and charter schools, the usual arguments about efficiency and quality were advanced to allow public money to go to for-profit institutes. The results were not surprising: for profit colleges proved to be disastrous for the students and the public. Far from being more efficient that public and non-profit colleges, the for-profits generally turned out to be significantly more expensive. They also tend to have significantly worse graduation and job placement rates than public and non-profit private schools. Students also accrue far more debt and make significant less money relative to public and private school students. These schools also sometimes go out of business, leaving students abandoned and often with useless credits that cannot transfer. They do, however, often excel at advertising—which explains how they lure in so many students when there are vastly better alternatives.

The public also literally paid the price—the for-profits receive a disproportionate amount of public money and students take out more student loans to pay for these schools and default on them more often. Far from being models of efficiency and quality, the for-profit colleges have often turned out to be little more than machines for turning public money into profits for a few. This is not to say that for-profit charter schools must become exploitation engines as well, but the disaster of for-profit colleges must be taken as a cautionary tale. While there are some who see our children as another resource to be exploited for profits, we should not allow this to happen.

Charter Schools III: Choice & Ideology

In my prior essay on charter schools, I considered the quality argument. The idea is that charter schools provide a higher quality alternative to public schools and should receive public money so that poorer families can afford to choose them. The primary problem with this argument is that it seems to make more sense to use public money to improve public schools—as opposed to siphoning money from them. I now turn to another aspect of choice, that of ideology (broadly construed).

While parents want to be able to choose a quality school for their children, some parents are also interested in having ideological alternatives to public schools. This desire forms the basis for the ideological choice argument for charter schools. While public schools are supposed to be as ideologically neutral as possible, some see public schools as ideologically problematic in two broad ways.

One way is that the public schools provide content and experiences that conflict with the ideology of some parents, most commonly with religious values. For example, public schools often teach evolution in science classes and this runs contrary to some theological views about the age of the earth and how species arise. As another example, some public schools allow students to use bathrooms and locker rooms based on their gender identity, which runs contrary to the values of some parents. As a third example, some schools teach history (such as that of slavery) in ways that run afoul of the ideology of parents. As a final example, some schools include climate change in their science courses, which might be rejected by some parents on political grounds.

A second way is that public schools fail to provide ideological content and experiences that parents want them to provide, often based on their religious views. For example, a public school might not provide Christian prayers in the classroom. As another example, a public school might not offer religious content in the science classes (such as creationism). As a final example, a public school might not offer abstinence only sex education, which can conflict with the values of some parents.

Charter schools, the argument goes, can offer parents an ideological alternative to public schools, thus giving them more choices in regards to the education of their children. Ideological charter schools can avoid offering content and experiences that parents do not want for their children while offering the content and experiences they want. For example, a private charter school could teach creationism and have facilities that conform to traditional gender identities.

It might be argued that parents already have such a choice: they can send their children to existing private schools. But, as noted in my first essay, many parents cannot afford to pay for such private schools. Since charter schools receive public money, parents who cannot afford to send their children to private ideological schools can send them to ideological charter schools, thus allowing them to exercise their right to choose. As an alternative to charter schools, some places have school voucher systems which allow students to attend private (often religious) schools using public money. The appeal of this approach is that it allows those who are less well-off to enjoy the same freedom of choice as the well off. After all, it seems unfair that the poor should be denied this freedom simply because they are poor. That said, there are some problems with ideological charter schools.

One concern about ideological charter schools is that that they would involve the funding of specific ideologies with public money. For example, public money going to a religious charter school would be a case of public funding of that religion, which is problematic in many ways in the United States. Those who favor ideological charter schools tend to do so because they are thinking of their own ideology. However, it is important to consider that allowing such charter schools opens the door to ideologies other than one’s own. For example, conservative Christian proponents of religious charter schools are no doubt thinking of public money going to Christian schools and are not considering that public money might also flow to Islamic charter schools or charter transgender training academies. Or perhaps they have already thought about how to ensure the money flows in accord with their ideology.

Another concern is that funding ideological charter schools with public money would be denying others their choice—there are many taxpayers who do not want their money going to fund ideologies they do not accept. For example, people who do not belong to a religious sect would most likely not want to involuntarily support that sect.

What might seem to be an obvious counter is that there are people who do not want their money going to public schools because of their ideological views. So, if it is accepted that public money can go to public schools, it should also be allowed to flow into ideological charter schools.

The reply to this is that public schools are controlled by the public, typically through elected officials. As such, people do have a choice in regards to the content and experiences offered by public schools. While people will not always get what they want, they do have a role in the democratic process. Public money is thus being spent in accord with what the public wants—as determined by this process. In contrast, the public does not have comparable choice when it comes to ideological charter schools—they are, by their very nature, outside of the public education system. This is not to say that there should not be such ideological schools, just that they should be in the realm of private choice rather than public funding.

To use a road analogy, imagine that Billy believes that it is offensive in the eyes of God for men and women to drive on the same roads and he does not want his children to see such blasphemy. Billy has every right to stay off the public roads and every right to start his own private road system on his property. However, he does not have the right to expect public road money to be diverted to his private road system so that he can exercise his choice.

Billy could, however, argue that as a citizen he is entitled to his share of the public road money. Since he is not using the public roads, the state should send him that share so that he might fund his private roads. He could get others to join him and pool these funds, thus creating his ideological charter roads. If confronted by the objection that the public should not fund his ideology, Billy could counter by arguing that road choice should not be a luxury that must be purchased. Rather, it is an entitlement that the state is obligated to provide.

This points to a key part of the matter about public funding for things like public roads and public education: are citizens entitled to access to the public systems or are they entitled to the monetary value of that access, which they should be free to use elsewhere? My intuition is that citizens are entitled to access to the public system rather than to a cash payout from the state. Citizens can elect to forgo such access, but this does not entitle them to a check from the state. As a citizen, I have the right to use the public roads and send any children I might have to the public schools. However, I am not entitled to public money to fund roads or schools that match my ideology just because I do not like the public system. As a citizen, I have the right to try to change the public systems—that is how democratic public systems are supposed to work. As such, while the ideological choice argument is appealing, it does not seem compelling.

Charter Schools I: Preliminaries & Monopolies

In November of 2016, president elect Trump selected Betsy DeVos as his Secretary of Education. While this appointment seems to have changed her mind about Common Core, DeVos has remained committed to expanding charter schools. Charter schools operate outside of the public-school system but are funded with public money. They can be privately owned and run as for-profit business. As might be suspected, they tend to be rather controversial.

Before discussing charter schools, I need to present the biasing factors in my background. Like most Americans, I attended public schools. Unlike some Americans, I got a very good public education that laid the foundation for my undergraduate and graduate education. Both of my parents were educators; my father taught math and computer science and my mother had a long career as a guidance counsellor. I ended up going to a private college and then to a public graduate school. This led to my current career as a philosophy professor at a state university. I belong to the United Faculty of Florida, the NEA and the AFT. As such, I am a union member. As might be suspected, my background inclines me to be suspicious of charter schools. As such, I will take special care to consider the matter fairly and objectively.

As with most politically charged debates, the battle over charter schools tends to be long on rhetoric and short on reasoned arguments. Devoted proponents of charter schools lament the ruin of public education, crusade for choice, and praise the profit motive as panacea for the woes of the academies. Energized enemies of charter schools regard them as plots against public good and profiteering at the expense of the children.

While there is some merit behind these rhetorical stances, charter schools should neither be accepted nor rejected based on mere rhetoric or ideological stances. As liberals and conservatives have both noted, there are serious problems in the American education system. Charter schools have been advanced as a serious proposal to address some of these problems and are worthy of objective consideration. I will begin with what can be called the monopoly argument in favor of charter schools.

Proponents of charter schools often assert that the state holds a monopoly on education and employ arguments by analogy to show why this is a bad thing. For example, the state monopoly on education might be compared to living in an area with only one internet service provider. This provider offers poor service, but residents are forced by law to pay for it and competition is forbidden. While this is probably better than not having any internet access at all, it is certainly a bad situation that could be improved by competition. If the analogy holds, then poor quality education could be improved by legalizing competition.

This analogy can also be used, obviously enough, to argue that people who do have children in school should not be forced to pay into the education system. This would be, to stick with the analogy, like making people who have no computers (including tablets and phones) pay for internet access they do not use. This is, however, another issue and I will return to the matter of charter schools.

While the analogy does have some appeal, the state does not have a monopoly on education. There are, obviously enough, private schools that operate without public money. These provide competition to public schools, thus showing that there is not a monopoly. By going through the appropriate procedures, anyone with the resources can create a private school. And anyone with the resources to afford a private school can attend. As such, there is already a competitive education industry in place that provides an alternative to public education. There is also the option of home schooling, which also breaks the alleged monopoly.

Supporters of charter schools can counter that there is a monopoly without charter schools. To be specific, without charter schools, public schools have a monopoly on public money. Charter schools, by definition, break this monopoly by allowing public funds to go to schools outside the state education system.

This can allow privately owned charter schools to enjoy what amounts to state subsidies, thus making it easier to start a privately-owned charter school than a privately funded private school. Those who are concerned about state subsidies might find this sort of thing problematic, perhaps because it seems to confer an unfair advantage over privately funded schools and funnels public money into private hands.

Supporters can counter these criticisms by turning them into virtues. Public money spent on charter schools is good exactly because it makes it easier to fund competing schools. Private schools without public funding need to operate in a free market—they must compete for customer money without the benefit of the state picking winners and losers. As such, there will not be very many privately funded schools. Charter schools benefit from the largesse of the state, although they do need to attract enough students. But this is made easier by the fact that charter school education is subsidized by public money.

As such, charter schools would break the public-school system’s monopoly on public money, although there is not a monopoly on education (since privately funded schools exist). The question remains as to whether or not breaking the funding monopoly is a good thing or not, which leads to the subject of the next essay in this series, that of choice.

The Return of Sophism

Scottie Nell Hughes, a Trump surrogate, presented her view of truth on The Diane Rehm Show. As she sees it:

Well, I think it’s also an idea of an opinion. And that’s—on one hand, I hear half the media saying that these are lies. But on the other half, there are many people that go, ‘No, it’s true.’ And so one thing that has been interesting this entire campaign season to watch, is that people that say facts are facts—they’re not really facts. Everybody has a way—it’s kind of like looking at ratings, or looking at a glass of half-full water. Everybody has a way of interpreting them to be the truth, or not truth. There’s no such thing, unfortunately, anymore as facts.

Since the idea that there are no facts seems so ridiculously absurd, the principle of charity demands that some alternative explanation be provided for Hughes’ claim. Her view should be familiar to anyone who has taught an introductory philosophy class. There is always at least one student who, often on day one of the class, smugly asserts that everything is a matter of opinion and thus there is no truth. A little discussion, however, usually reveals that they do not really believe what they think they believe. Rather than thinking that there really is no truth, they merely think that people disagree about what they think is true and that people have a right to freedom of belief. If this is what Hughes believes, they I have no dispute with her: people believe different things and, given Mill’s classic arguments about liberty, it seems reasonable to accept freedom of thought.

But, perhaps, the rejection of facts is not as absurd as it seems. As I tell my students, there are established philosophical theories that embrace this view. One is relativism, which is the view that truth is relative to something—this something is typically a culture, though it could also be (as Hughes seems to hold) relative to a political affiliation. One common version of this is aesthetic relativism in which beauty is relative to the culture, so there is no objective beauty. The other is subjectivism, which is the idea that truth is relative to the individual. Sticking with an aesthetic example, the idea that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” is a subjectivist notion. On this view, there is not even a cultural account of beauty, beauty is entirely dependent on the observer. While Hughes does not develop her position, she seems to be embracing political relativism or even subjectivism: “And so Mr. Trump’s tweet, amongst a certain crowd—a large part of the population—are truth. When he says that millions of people illegally voted, he has some—amongst him and his supporters, and people believe they have facts to back that up. Those that do not like Mr. Trump, they say that those are lies and that there are no facts to back it up.”

If Hughes takes the truth to be relative to the groups (divided by their feelings towards Trump), then she is a relativist. In this case, each group has its own truth that is made true by the belief of the group. If she holds truth to be dependent on the individual, then she would be a subjectivist. In this case, each person has her own truth, but she might happen to have a truth that others also accept.

While some might think that this view of truth in politics is something new, it is ancient and dates back at least to the sophists of ancient Greece. The sophists presented themselves as pragmatic and practical—for a fee, they would train a person to sway the masses to gain influence and power. One of the best-known sophists, thanks to Plato, was Protagoras—he offered to teach people how to succeed.

The rise of these sophists is easy to explain—a niche had been created for them. Before the sophists came the pre-Socratic philosophers who argued relentlessly against each other. Thales, for example, argued that the world is water. Heraclitus claimed it was fire. These disputes and the fact the arguments tended to be well-balanced for and against any position, gave rise to skepticism. This is the philosophical view that we lack knowledge. Some thinkers embraced this and became skeptics, others went beyond skepticism.

Skepticism often proved to be a gateway drug to relativism—if we cannot know what is true, then it seems sensible that truth is relative. If there is no objective truth, then the philosophers and scientist are wasting their time looking for what does not exist. The religious and the ethical are also wasting their time—there is no true right and no true wrong. But accepting this still leaves twenty-four hours a day to fill, so the question remained about what a person should do in a world without truth and ethics. The sophists offered an answer.

Since searching for truth or goodness would be pointless, the sophists adopted a practical approach. They marketed their ideas to make money and offered, in return, the promise of success. Some of the sophists did accept that there were objective aspects of reality, such as those that would fall under the science of physics or biology. They all rejected the idea that what philosophers call matters of value (such as ethics, politics, and economics) are objective, instead embracing relativism or subjectivism.

Being practical, they did recognize that many of the masses professed to believe in moral (and religious) values and they were aware that violating these norms could prove problematic when seeking success. Some taught their students to act in accord with the professed values of society. Others, as exemplified by Glaucon’s argument for the unjust man in the Ring of Gyges story of the Republic, taught their students to operate under the mask of morality and social values while achieving success by any means necessary. These views had a clear impact on lying.

Relativism still allows for there to be lies of a sort. For those who accept objective truth, a lie (put very simply) an intentional untruth, usually told with malicious intent. For the relativist, a lie would be intentionally making a claim that is false relative to the group in question, usually with malicious intent. Going back to Hughes’ example, to Trump’s true believers Trump’s claims are true because they accept them. The claims that Trump is lying would be lies to the Trump believers, because they believe that claim is untrue and that the Trump doubters are acting with intent. The reverse, obviously enough, holds for the Trump doubters—they have their truth and the claims of the Trump believers are lies. This approach certainly seems to be in use now, with some pundits and politicians embracing the idea that what they disagree with is thus a lie.

Relativism does rob the accusation of lying of much of its sting, at least for those who understand the implications of relativism. On this view a liar is not someone who is intentionally making false claims, a liar is someone you disagree with. This does not mean that relativism is false, it just means that accusations of untruth become rhetorical tools and emotional expressions without any, well, truth behind them. But, they serve well in this capacity as a tool to sway the masses—as Trump showed with great effect. He simply accuses those who disagree with him of being liars and many believe him.

I have no idea whether Trump has a theory of truth or not, but his approach is utterly consistent with sophism and the view expressed by Hughes. It would also explain why Trump does not bother with research or evidence—these assume there is a truth that can be found and supported. But if there is no objective truth and only success matters, then there is no reason not to say anything that leads to success.

There are, of course, some classic problems for relativism and sophism. Through Socrates, Plato waged a systematic war on relativism and sophism—some of the best criticisms can be found in his works.

One concise way to refute relativism is to point out that relativism requires a group to define the truth. But, there is no way principled way to keep the definition of what counts as a group of believers from sliding to there being a “group” of one, which is subjectivism. The problem with subjectivism is that if it is claimed that truth is entirely subjective, then there is no truth at all—we end up with nihilism. One obvious impact of nihilism is that the sophists’ claim that success matters is not true—there is no truth. Another important point is that relativism about truth seems self-refuting: it being true requires that it be false. This argument seems rather too easy and clever by far, but it does make an interesting point for consideration.

In closing, it is fascinating that Hughes so openly presented her relativism (and sophism). Most classic sophists advocated, as noted above, operating under a mask of accepting conventional moral values. But, just perhaps, we are seeing a bold new approach to sophism: one that is trying to shift the values of society to openly accepting relativism and embracing sophism. While potentially risky, this could yield considerable political advantages and sophism might see its day of triumph. Assuming that it has not already done so.

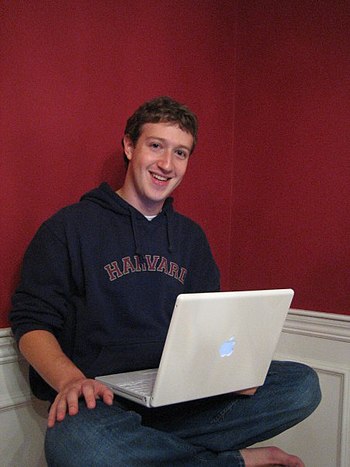

Fake News II: Facebook

While a thorough analysis of the impact of fake news on the 2016 election will be an ongoing project, there are excellent reasons to believe that it was a real factor. For example, BuzzFeed’s analysis showed how the fake news stories outperformed real news stories. When confronted with the claim that fake news on Facebook influenced the election results, Mark Zuckerberg’s initial reaction was denial. However, as critics have pointed out, to say that Facebook does not influence people is to tell advertisers that they are wasting their money on Facebook. While this might be the case, Zuckerberg cannot consistently pitch the influence of Facebook to his customers while denying that it has such influence. One of these claims must be mistaken.

While my own observations do not constitute a proper study, I routinely observed people on Facebook treating fake news stories as if they were real. In some cases, these errors were humorous—people had mistaken satire for real news. In other cases, they were not so funny—people were enraged over things that had not actually happened. There is also the fact that public figures (such as Trump) and pundits repeat fake news stories acquired from Facebook (and other sources). As such, fake news does seem to be a real problem on Facebook.

It could be claimed that the surge in fake news is an anomaly, that it was the result of a combination of factors that will probably not align again. One factor would be having presidential candidates so disliked that people would find even fake stories plausible. A second factor would be Trump’s relentless spewing of untruths, thus creating an environment friendly to fake news. A third factor would be Trump ratcheting the Republican attack on the mainstream news media to 11, thus pushing people towards other news sources and undercutting fact checking and critical reporting. Provided that these and similar factors change, fake news could decline significantly.

While this could happen, it seems that some of these factors will continue. As president elect, Trump has continued to spew untruths and the attacks on the mainstream media continue. The ecosystem thus seems ideal for fake news to thrive. As such, it seems likely that while the fake news will decline to some degree, it will remain a factor as long as it is influential or profitable. This is where Facebook comes in—while fake news sites can always have their own web pages, Facebook serves up the fake news to a huge customer base and thus drives the click based profits (thanks to things like Google advertising) of these sites. This powerful role of Facebook gives rise to moral concerns about its accountability.

One obvious approach is to claim that Facebook has no moral responsibility in regards to policing fake news. This could be argued by drawing an analogy between Facebook and a delivery company like UPS or Fedex. Rather than delivering physical packages, Facebook is delivering news.

A delivery company is responsible for delivering a package intact and within the specified time. However, it does not have a moral responsibility regarding what is shipped. Suppose, for example, that businesses arose selling “Artisanal Macedonian Pudding” and purport that it is real pudding. But, in fact, it is a blend of sugar and shit that looks like pudding. Some customers fail to recognize it for what it is and happily shovel it into their pudding port; probably getting sick—but still loving the taste. If the delivery company were criticized for delivering the pudding, they would be right to say that they are not responsible for the “pudding”—they merely deliver packages. The responsibility lies with the “pudding” companies. And the customers for not recognizing sugary shit as shit. If the analogy holds, then Facebook is just delivering fake news as the delivery company delivers “Macedonian Pudding” and is not morally responsible for the contents of the packages.

A possible counter to this is that once Facebook knows that a site is a fake news site, then they are morally responsible for continuing to deliver the fake news. Going with the delivery analogy, once the delivery company is aware that “Artisanal Macedonian Pudding” is sugar and shit, they have a moral obligation to cease their business with those making this dangerous product. This could be countered by arguing that as long as the customer wants the package of “pudding”, then it is morally fine for the delivery company to provide it. However, this would seem to require that the customer knows they are getting sugar and shit—otherwise the delivery company is knowingly participating in a deceit and the distribution of a harmful product. This would seem to be morally wrong.

Another approach to countering this argument is to use a different analogy: Facebook is not like a delivery company, it is like a restaurant selling the product. Going back to the “pudding”, a restaurant that knowingly purchased and served sugar and shit as pudding would be morally accountable for this misdeed. By this analogy, once Facebook knows they are profiting from selling fake news, they are morally accountable and in the wrong if they fail to address this. A possible response to this is to contend that Facebook is not selling the fake news; but this leads to the question of what Facebook is doing.

One way to look at Facebook is that the fake news is just like advertising in any other media. In this case, the company selling the ad is not morally accountable for the content of the ad of the quality of the product. Going back to the “pudding”, if one company is selling sugar and shit as pudding, the company running the advertising is not morally responsible. The easy counter to this is that once the company selling the ads knows that the “pudding” is sugar and shit, then they would be morally wrong to be a party to this harmful deception. Likewise for Facebook treating fake news as advertising.

Another way to look at Facebook is that it is serving as a news media company and is in the business of providing the news. Going back to the pudding analogy, Facebook would be in the pudding business as a re-seller, selling sugar and shit as real pudding. This would seem to obligate Facebook to ensure that the news it provides is accurate and to not distribute news it knows it is fake. This assumes a view of journalistic ethics that is obviously not universally accepted, but a commitment to the truth seems to be a necessary bedrock of any worthwhile media ethics.

Fake News I: Critical Thinking

While fake news presumably dates to the origin of news, the 2016 United States presidential election saw a huge surge in the volume of fakery. While some of it arose from partisan maneuvering, the majority seems to have been driven by the profit motive: fake news drives revenue generating clicks. While the motive might have been money, there has been serious speculation that the fake news (especially on Facebook) helped Trump win the election. While those who backed Trump would presumably be pleased by this outcome, the plague of fake news should be worrisome to anyone who values the truth, regardless of their political ideology. After all, fake news could presumably be just as helpful to the left as the right. In any case, fake news is clearly damaging in regards to the truth and is worth combating.

While it is often claimed that most people simply do not have the time to be informed about the world, if someone has the time to read fake news, then they have the time to think critically about it. This critical thinking should, of course, go beyond just fake news and should extend to all important information. Fortunately, thinking critically about claims is surprisingly quick and easy.

I have been teaching students to be critical about claims in general and the news in particular for over two decades and what follows is based on what I teach in class (drawn, in part, from the text I have used: Critical Thinking by Moore & Parker). I would recommend this book for general readers if it was not, like most text books, absurdly expensive. But, to the critical thinking process that should be applied to claims in general and news in particular.

While many claims are not worth the bother of checking, others are important enough to subject to scrutiny. When applying critical thinking to a claim, the goal is to determine whether you should rationally accept it as true, reject it as false or suspend judgment. There can be varying degrees of acceptance and rejection, so it is also worth considering how confident you should be in your judgment.

The first step in assessing a claim is to match it against your own observations, should you have relevant observations. While observations are not infallible, if a claim goes against what you have directly observed, then that is a strike against accepting the claim. This standard is not commonly used in the case of fake news because most of what is reported is not something that would be observed directly by the typical person. That said, sometimes this does apply. For example, if a news story claims that a major riot occurred near where you live and you saw nothing happen there, then that would indicate the story is in error.

The second step in assessment is to judge the claim against your background information—this is all your relevant beliefs and knowledge about the matter. The application is fairly straightforward and just involves asking yourself if the claim seems plausible when you give it some thought. For example, if a news story claims that Hillary Clinton plans to start an armed rebellion against Trump, then this should be regarded as wildly implausible by anyone with true background knowledge about Clinton.

There are, of course, some obvious problems with using background information as a test. One is that the quality of background information varies greatly and depends on the person’s experiences and education (this is not limited to formal education). Roughly put, being a good judge of claims requires already having a great deal of accurate information stored away in your mind. All of us have many beliefs that are false; the problem is that we generally do not know they are false. If we did, then we would no longer believe them.

A second point of concern is the influence of wishful thinking. This is a fallacy (an error in reasoning) in which a person concludes that a claim is true because they really want it to be true. Alternatively, a person can fallaciously infer that a claim is false because they really want it to be false. This is poor reasoning because wanting a claim to be true or false does not make it so. Psychologically, people tend to disengage their critical faculties when they really want something to be true (or false).

For example, someone who really hates Hillary Clinton would want to believe that negative claims about her are true, so they would tend to accept them. As another example, someone who really likes Hillary would want positive claims about her to be true, so they would accept them.

The defense against wishful thinking of this sort is to be on guard against yourself by being aware of your biases. If you really want something to be true (or false), ask yourself if you have any reason to believe it beyond just wanting it to be true (or false). For example, I am not a fan of Trump and thus would tend to want negative claims about him to be true—so I must consider that when assessing such claims.

A third point of concern is related to wishful thinking and could be called the fallacy of fearful/hateful thinking. While people tend to believe what they want to believe, they also tend to believe claims that match their hates and fears. That is, they believe what they do not want to believe. Fear and hate impact people in a very predictable way: they make people stupid when it comes to assessing claims.

For example, there are Americans who hate the idea of Sharia law and are terrified it will be imposed on America. While they would presumably wish that claims about it being imposed were false, they will often believe such claims because it corresponds with their hate and fear. Ironically, their great desire that it not be true motivates them to feel that it is true, even when it is not.

The defense against this is to consider how a claim makes you feel—if you feel hatred or fear, you should be very careful in assessing the claim. If a news claims seems tailored to push your buttons, then there is a decent chance that it is fake news. This is not to say that it must be fake, just that it is important to be extra vigilant about claims that are extremely appealing to your hates and fears. This is a very hard thing to do since it is easy to be ruled by hate and fear.

The third step involves assessing the source of the claim. While the source of a claim does not guarantee the claim is true (or false), reliable sources are obviously more likely to get things right than unreliable sources. When you believe a claim based on its source, you are making use of what philosophers call an argument from authority. The gist of this reasoning is that the claim being made is true because the source is a legitimate authority on the matter. While people tend to regard as credible sources those that match their own ideology, the rational way to assess a source involves considering the following factors.

First, the source needs to have sufficient expertise in the subject matter in question. One rather obvious challenge here is being able to judge that the specific author or news source has sufficient expertise. In general, the question is whether a person (or the organization in general) has the relevant qualities and these are assessed in terms of such factors as education, experience, reputation, accomplishments and positions. In general, professional news agencies have such experts. While people tend to dismiss Fox, CNN, and MSNBC depending on their own ideology, their actual news (as opposed to editorial pieces or opinion masquerading as news) tends to be factually accurate. Unknown sources tend to be lacking in these areas. It is also wise to be on guard against fake news sources pretending to be real sources—this can be countered by checking the site address against the official and confirmed address of professional news sources.

Second, the claim made needs to be within the source’s area(s) of expertise. While a person might be very capable in one area, expertise is not universal. So, for example, a businessman talking about her business would be an expert, but if she is regarded as a reliable source for political or scientific claims, then that would be an error (unless she also has expertise in these areas).

Third, the claim should be consistent with the views of the majority of qualified experts in the field. In the case of news, using this standard involves checking multiple reliable sources to confirm the claim. While people tend to pick their news sources based on their ideology, the basic facts of major and significant events would be quickly picked up and reported by all professional news agencies such as Fox News, NPR and CNN. If a seemingly major story does not show up in the professional news sources, there is a good chance it is fake news.

It is also useful to check with the fact checkers and debunkers, such as Politifact and Snopes. While no source is perfect, they do a good job assessing claims—something that does not make liars very happy. If a claim is flagged by these reliable sources, there is an excellent chance it is not true.

Fourth, the source must not be significantly biased. Bias can include such factors as having a very strong ideological slant (such as MSNBC and Fox News) as well as having a financial interest in the matter. Fake news is typically crafted to feed into ideological biases, so if an alleged news story seems to fit an ideology too well, there is a decent chance that it is fake. However, this is not a guarantee that a story is fake—reality sometimes matches ideological slants. This sort of bias can lead real news sources to present fake news; you should be critical even of professional sources-especially when they match your ideology.

While these methods are not flawless, they are very useful in sorting out the fake from the true. While I have said this before, it is worth repeating that we should be even more critical of news that matches our views—this is because when we want to believe, we tend to do so too easily.

White Nationalism II: The BLM Argument

While there are some varieties of white nationalism, it is an ideology committed to the creation and preservation of a nation comprised entirely of whites (or at least white dominance of the nation). While some white nationalists honestly embrace their racism, others prefer to present white nationalism in a more pleasant guise. Some advance arguments to show that it should be accepted as both good and desirable.

While it is not limited to using Black Lives Matter, I will dub one of the justifying arguments “the BLM argument” and use BLM as my main example when discussing it. The argument typically begins by pointing out the existence of “race-based” identity groups such as Black Lives Matters, Hispanic groups, black student unions and so on. The next step is to note that these groups are accepted, even lauded, by many (especially on the left). From this it is concluded that, by analogy, white identity groups should also be accepted, if not lauded.

If analogies are not one’s cup of tea, white identity groups can be defended on the grounds of consistency: if the existence of non-white identity groups is accepted, then consistency requires accepting white identity groups.

From a logical standpoint, both arguments have considerable appeal because they involve effective methods of argumentation. However, consistency and analogical arguments can both be challenged and this challenge can often be made on the same basis, that of the principle of relevant difference.

The principle of relevant difference is the principle that similar things must be treated in similar ways, but that relevantly different things can be justly treated differently. For example, if someone claimed that it was fine to pay a woman less than a man simply because she is a woman, then that would violate the principle of relevant difference. If it was claimed that a male worker deserves more pay because he differs from a female co-worker in that he works more hours, then this would fit the principle. In the case of the analogical argument, a strong enough relevant difference would break the analogy and show that the conclusion is not adequately supported. In the case of the consistency argument, showing a strong enough relevant difference would justify treating two things differently because sufficiently different things can justly be treated differently.

A white nationalist deploying the BLM argument would contend that although there are obviously differences between BLM and a white nationalist group, these differences are not sufficient to allow condemnation of white nationalism while accepting BLM. Put bluntly, it could be said that if black groups are morally okay, then so are white groups. On the face of it, this generally reasoning is solid enough. It would be unprincipled to regard non-white groups as acceptable while condemning white groups merely because they are white groups.

One way to respond to this would be to argue that all such groups are unacceptable; perhaps because they would be fundamentally racist in character. This would be a consistent approach and has some appeal—accepting these sorts of identity groups is to accept race identification as valid; which seems problematic.

Another approach is to make relevant difference arguments that establish strong enough differences between white nationalist groups and groups like BLM and Hispanic student unions. There are many options and I will consider a few.

One option is to argue that such an identity group is justified when the members of that group are identified by others and targeted on this basis for mistreatment or oppression. In this case, the group identity would be imposed and acknowledged as a matter of organizing a defense against the mistreatment or oppression. BLM members can make the argument that black people are identified as blacks and mistreated on this basis by some police. As such, BLM is justified as a defensive measure against this mistreatment. Roughly put, blacks can justly form black groups because they are targeted as blacks. The same reasoning would apply to other groups aimed at protection from mistreatment aimed at specific identity groups.

Consistency would require extending this same principle to whites. As such, if whites are being targeted for mistreatment or oppression because they are white, then the formation of defensive white identity groups would be warranted. Not surprisingly, this is exactly the argument that white groups often advance: they allege they are victims and are acting to protect themselves.

While white groups have a vast and varied list of the crimes they believe are being committed against them as whites, they are fundamentally mistaken. While crimes are committed against white people and there are white folks who are suffering from things like unemployment and opioid addiction, these are not occurring because they are white. They are occurring for other reasons. While it is true that the special status of whites is being challenged, and has eroded over the years, the loss of such unfair and unwarranted advantages in favor of greater fairness is not a moral crime. The belief in white victimhood is the result of willful delusion and intentional deceit and is not grounded in facts.

This line of argument does, however, remain open to empirical research. If it can be shown with objective evidence that whites are subject to general mistreatment and oppression because they are whites, then defensive white groups would be justified on these grounds. While I am aware that people can find various videos on YouTube purporting to establish the abuse of whites as whites, one must distinguish between anecdotal evidence and adequate statistical support. For example, if fatal DWW (Driving While White) incidents started occurring at a statistically significant level, then it would be worth considering the creation of WLM (White Lives Matter).

A second option is to consider the actions and goals of the group in question. If a group has a morally acceptable goal and acts in ethical ways, then the group would be morally fine. However, a group that had morally problematic goals or acted in immoral ways would be relevantly different from groups with better goals and methods.

While BLM does have its detractors, its avowed goal is “is working for a world where Black lives are no longer systematically and intentionally targeted for demise.” This seems to be a morally commendable goal. While BLM is often condemned by the likes of Fox News for their protests, the organization certainly seems to be operating in accord with a non-violent approach to protesting. As such, its general methodology is at least morally acceptable. This is, of course, subject to debate and empirical investigation. If, for example, it was found that BLM were organizing the murder of police officers, then that would make the group morally wrong.

White groups could, of course, have morally acceptable goals and methods. For example, if a white group was created in response to the surge in white people dying from opioids and they focused on supporting treatment of white addicts, then such a group would seem to be morally fine.

However, there are obviously white groups that have evil goals and use immoral methods. White supremacy groups, such as the KKK, are the usual examples of such groups. The white nationals also seem to be an immoral group. The goal of white dominance and the goal of establishing a white nation are both to be condemned, albeit not always for the same reasons. While the newly “mainstreamed” white nationalists are not explicitly engaged in violence, they do make use of a systematic campaign of untruths and encourage hatred. The connections of some to Nazi ideology is also extremely problematic.

In closing, while it is certainly possible to have white identity groups that are morally acceptable, the white nationalists are not among them. It is also worth noting that all identity groups might be morally problematic.

25 comments