A Philosopher’s Blog 2016 free on Amazon (12/31/2016-1/4/2017)

This book contains essays from the 2016 postings of A Philosopher’s Blog. Subjects range from the metaphysics of guardian angels to the complicated ethics of guns. There are numerous journeys into the realm of political philosophy and some forays into the kingdom of fake news.

This book contains essays from the 2016 postings of A Philosopher’s Blog. Subjects range from the metaphysics of guardian angels to the complicated ethics of guns. There are numerous journeys into the realm of political philosophy and some forays into the kingdom of fake news.

The essays are short, but substantial—yet approachable enough to not require a degree in philosophy.

The book, in Kindle format, will be free on Amazon from 12/31/2016 until 1/4/2017. This deal applies worldwide.

US Link: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B01MT40YX0

Consent of the Governed

Plato, through the character of Socrates, advances a now classic argument against democracy. When it comes to a matter that requires knowledge and skill, such as a medical issue, it would be foolish to decide by having the ignorant vote on the matter. Those who have good sense turn to those who have the knowledge and skill needed to make a good decision.

Political matters, such as deciding what policies to adopt regarding immigration, require knowledge and skill. As such, it would be foolish to make decisions by having the ignorant and unskilled vote on such matters. Picking a competent leader also requires knowledge and skill and thus it would be foolish to leave it to those lacking these attributes.

In the abstract, this argument is compelling: as with all tasks that require competence, it would be best to have the competent make the decisions and the incompetent should remain on the sidelines. There are, however, various counters to this argument.

One appealing argument assumes people have a moral right to a role in decisions that impact them, even if they are not likely to make the best (or even good) choices. Consider, for example, something as simple as choosing a meal. Most people will not select the most nutritious or even most delicious option, thus making a bad choice. However, compelling people against their will to eat a meal, even if it is the best for them, seems to be morally problematic. At least when it comes to adults. Naturally, an argument can be made that people who routinely make poor health choices would be better off being compelled to eat healthy foods—which is the heart of this dispute between democracy and being ruled by those with the knowledge and skills to make better decisions.

Another approach is to use the context of the state of nature. This is a philosophical device developed by thinkers like Locke, Hobbes and Rousseau in which one is asked to imagine a world without a political system in place, a world in which everyone is equal in social status. In this world, there are no kings, presidents, lawyers, police or other such socially constructed positions of hierarchy. It is also assumed there is nothing supernatural conferring a right to rule (such as the make-believe divine right of kings). In such a context, the obvious question is that of what would give a person the right to rule over others.

As a practical matter, the strongest might coerce others into submission, but the question is one of the right to rule and not a question of what people could do. Given these assumptions, it would seem that no one has the right to be the boss over anyone else—since everyone is equal in status. What would be required, and what has often been argued for, is that the consent of the governed would be needed to provide the ruler with the right to rule. This is, of course, the assumed justification for political legitimacy in the United States and other democratic countries.

If it is accepted that political legitimacy is based on the consent of the governed, then the usual method of determining this consent is by voting. For a country to continue as one country it must also be accepted that the numerical minority will go along with the vote of the numerical majority—otherwise, as Locke noted, the country would be torn asunder. This is, as has been shown in the United States, consistent with having certain things (such as rights) that are protected from the possible tyranny of the majority.

If voting is accepted in this role, then maintaining political legitimacy would seem to require two things. The first is that there must be reliable means of assuring that fraud does not occur in elections. The United States has done an excellent job at this. While there are some issues with the accuracy of voter lists (people who move or die often remain on lists for years), voter fraud is almost non-existent, despite unsupported assertions to the contrary.

The second is that every citizen who wishes to vote must have equal and easy access to the voting process. To the degree that citizens are denied this equal and easy access, political legitimacy is decreased. This is because those who are deterred or prevented from voting are denied the opportunity to provide their consent. This excludes them from falling under the legitimate authority of the government. It also impacts the legitimacy of the government in general. Since accepting a democratic system means accepting majority rule, excluding voters impacts this. After all, one does not know how the excluded voters would have voted, thus calling into question whether the majority is ruling or not.

Because of this, the usual attempts to deter voter participation are a direct attack on political legitimacy in the United States. These include such things as voter ID laws, restrictions on early voting, unreasonable limits on polling hours, cutting back on polling places and so on.

In contrast, efforts to make voting easier and more accessible (consistent with maintaining the integrity of the vote) increase political legitimacy. These include such things as early voting, expanded voting hours, providing free transportation to polling stations, mail in voting, online voter registration and so on. One particularly interesting idea is automatic voter registration.

It could be argued that citizens have an obligation to overcome inconveniences and even obstacles to vote; otherwise they are lazy and unworthy. While it is reasonable to expect citizens to put in a degree of effort, the burden of access rests on the government. While it is the duty of a citizen to vote, it is the duty of the government to allow citizens to exercise this fundamental political right without undue effort. That is, the government needs to make it as easy and convenient as possible. This can be seen as somewhat analogous to the burden of proof: the citizen is not obligated to prove their innocence; the state must prove their guilt.

It could be objected that I only favor easy and equal access to the voting process because I am registered as a Democrat and Democrats are more likely to win when voter turnout is higher. If the opposite were true, then I would surely change my view. The easy and obvious reply to this objection is that it is irrelevant to the merit of the arguments advanced above. Another reply is that I actually do accept majority rule and even if Democrats were less likely to win with greater voter turnout, I would still support easy and equal access. And would do so for the reasons given above.

Exploiting Terror

Terrorism, like assassination, is violence with a political purpose. An assassination might also be intended to create terror, but the main objective is to eliminate a specific target. In contrast, terrorism is not aimed at elimination of a specific target; the goal is to create fear and almost any victims will suffice.

An individual terrorist might have any number of motives ranging from the ideological to the personal. Perhaps the terrorist sincerely believes that God loves the murder of innocents. Perhaps the terrorist was rejected by someone they were infatuated with and is lashing out in rage. While speculation into the motives of such people is certainly interesting and important, behind all true terrorism lies a political motivation—although the motivation might be on the part of those other than the person conducting the actual act.

While a terrorist attack can create fear on the local level by itself, terrorists need the media and social media to spread their terror on a large scale. The media is always happy to oblige and provide extensive coverage. While this coverage can be defended on the grounds that people have a right to know the facts, the coverage does have some important and (hopefully) unintended consequences.

One effect of extensive media coverage is to serve as an impact multiplier—the whole world is informed of the terrorist act and the group that claims credit gains terrorist credibility and status. This improves the influence of the group and enhances its ability to recruit—the group is essentially getting free advertising. Assuming that aiding terrorists is morally wrong, this coverage is morally problematic.

A second effect of the coverage is that it fuels the spotlight fallacy. This is a fallacy in which a person estimates the chances that something will happen based on how often they hear about it rather than based on how often it actually occurs. Terrorist attacks in the West are very rare and what Americans should really be worried about, based on statistics, is poor lifestyle choices that are encouraged and aided by industry. These include the use of tobacco, over consumption of alcohol, misuse of pain killers, eating unhealthy food and driving automobiles. Since terrorist attacks are covered relentlessly in the news and the leading causes of premature death are not, it is easy for people to overestimate the danger posed by terrorism. And underestimate what will probably kill them.

A third effect of coverage is that it can make people victims of the fallacy of misleading vividness. This fallacy occurs when a person overestimates the chances that something will occur based on how vivid or extreme the event is. While the media typically exercises some restraint in it coverage, the depiction is obviously scary to most and this can cause people to psychologically overestimate the threat.

Whether a person falls victim to the spotlight fallacy or misleading vividness, the end result is the same: the person overestimates the danger and is thus more afraid then they should be. This has beneficial effects for those who wish to exploit this fear.

Obviously enough, the terrorists aim to exploit the fear they create—they want people in the West to believe that they are in terrible danger and face an existential threat. Lacking the capacity to engage in actual war, they must make use of the strategy of terror. These two fallacies are critical weapons in their war and people who fall victim to them have allowed the terrorists to win.

One of the ironies of terrorism is that there are politicians in the West who exploit the fear created by terrorists and use it to influence people for their political ends. While they do not deploy the terrorists, they benefit from the attacks as much as the masters of the terrorists do.

Not surprisingly, they make use of some classic fallacies: appeal to fear and appeal to anger. An appeal to fear occurs when something that is supposed to create fear is offered in place of actual evidence. In the case of an appeal to anger, the same sort of thing is done, only with anger. This is not to say that something that might make a person afraid or angry cannot serve as actual evidence; it is that these fallacies offer no reasons to support the claim in question and only appeal to the emotions.

Interestingly, terrorists like ISIS and the Western political groups that exploit them have very similar objectives. Both want to present the fight as a clash of cultures, the West (and Christianity) against Islam. They both want this for similar reasons—to increase the number of their followers and to keep the conflict going so it can be exploited to fuel their political ambitions. If Muslims are accepted by the Western countries, then the terrorist groups lose influence and propaganda tools—and thus lose recruits. If Muslims accept the West, then the Western political groups exploiting fear of Islam also lose influence and propaganda tools—and thus lose recruits.

Both the terrorists and their Western exploiters want to encourage Westerners to be afraid of refugees coming from conflict areas in the Middle East. After all, if the West takes in refugees and treats them well, this is a loss of recruits and propaganda for the terrorists. It is also a loss for those who try to build political power on fear and hatred of refugees.

If refugees have no way to escape conflict, they will be forced to be either victims or participants. Children who grow up without education, stability and opportunity will also be much easier to recruit into terrorist groups. This is all in the interest of the terrorists; but also the Western political groups who want to exploit terrorism. After all, these groups are founded on identity politics and need a scary “them” to contrast with “us.”

This is not to say that the West should not be on guard against possible attacks or that the West should not vet refugees. My main point is that over reacting to terrorism only serves the ends of the wicked, be they actual terrorists or those in the West who would exploit this terror to gain power.

Is the State a Business?

While people who voted for Donald Trump give various reasons for their choice, some say that they chose him because he is a businessman and they view government as a business. While some might be tempted to dismiss this as mere parroting of empty political rhetoric, the question of whether the state is a business is well worth considering.

The state (that is, the people who occupy various roles) does engage in considerable business like behavior. For example, the state routinely engages in contracts for products and services. As another example, the state does charge for some goods and services. As a third example, the state does engage in economic deals with other states. As such, it is indisputable that the state does business. However, this is rather distinct from being a business. To use an analogy, individuals routinely interact with businesses, yet this does not make them businesses. So, for the state to be a business, there must be something more to it than merely engaging in some business-like behavior.

One approach is the legal one. Businesses tend to be defined by the relevant laws, especially corporations. As it now stands, the United States government does not seem to be legally defined as a business. This could, of course, be changed with a law. But such a legal status would not, by itself, be terribly interesting philosophically. After all, the question is not “is there a law that says the state is a business?” but “is the state a business?”

To take the usual Socratic approach, the proper starting point is working out a useful definition of business. Since this a short essay, the definition also needs to be succinct. The easy and obvious way to define a business is as an entity that provides goods or services (which can be very abstract) in return for economic compensation with the goal of making a profit.

While there are government owned corporations that operate as businesses, the government itself does not seem to fit this definition. One reason is that while the state does provide goods and services, these are typically provided without explicit economic compensation. For example, while taxpayers do pay taxes, they do not typically pay explicit bills for what they have received. Some also receive goods and services without providing any compensation to the state. For example, some corporations can exploit the tax laws so they can avoid paying any taxes.

While this seems to indicate that the state is not a business (or is perhaps a badly run business), there is also the question of whether the state should operate this way. In his essay on civil disobedience, Henry David Thoreau suggested that people should have an essentially transactional relationship with the state. That is, they should pay for the goods and services they use, as they would do with any business. For example, a person who used the state roads would pay for this use via the highway tax. This approach does have some appeal.

One part of the appeal is ethical—Thoreau’s motivation was not to be a cheapskate, but to avoid contributing to government activities he regarded as morally wrong (two evils he wished to avoid funding were the Mexican-American war and slavery). Since the state routinely engages in activities that various citizens find morally problematic (such as subsidizing corporations), this would allow people to act in accord with their values and influence the state directly by voting with their dollars. The idea is that just as a conventional business will give the customers what they want, the state as business would do the same thing.

Another part of the appeal is economic—people would only pay for what they use and many probably believe that this approach would cost them less than paying taxes. For example, a person who has no kids in the public schools would not pay for the schools, thus saving them money. There are, of course, some practical concerns that would need to be worked out here. For example, should people be allowed to provide their own police and fire services and thus avoid paying for these services? As another example, there is the challenge of working out how the billing would be calculated and implemented. Fortunately, this is technical challenge that existing business have already addressed, albeit on a much smaller scale. However, this is not just a matter of technical challenges.

A rather obvious problem is that there are people and organizations who cannot afford to pay for the services they need (or want) from the state. For example, people who receive food stamps or unemployment benefits cannot pay the value for these goods. If they had the money to pay for them, they would not need them. As another example, companies that benefit from United States military interventions and foreign policy would be hard pressed to pay the full cost of these operations. As a third example, it would be absurd for companies that receive subsidies to pay for these subsidies—if they did, they would not be subsidies. The company would just hand the state money to hand back to it, which would merely be a waste of time. The same would apply to student financial aid and similar individual subsidies.

It could be replied that this is acceptable—those who cannot pay for the goods and services will be forced to work harder to be able to pay for what they need. Just as a person who wants to have a car must work to earn it, a person who wants to have police protection must also work to earn it. If they cannot do so, then it will become a self-correcting problem. Naturally, the state could engage in some limited charity, much like businesses sometimes do so for customers who are down on their luck but could return to being sources of profits. The state could also extend credit to citizens who are down on their luck or even conscript them so they can work off their debts to the state.

The counter to this is to argue that the state should not operate like a business here—that it has obligations that go beyond those imposed by payments for goods or services to be received. The challenge is, of course, to argue for the basis of this obligation.

A second reason the state is not a business is that it does not operate to make a profit. This is not merely because the United States government spends more than it brings in, but because it does not even aim at making a profit. This is not to say that profits are not made by individuals, just that the state as a whole does not run on this model. This is presumably fortunate for the state—few other entities could operate at a deficit for so long without ceasing to be.

There is, of course, the question of whether the state should aim to operate at a profit. This, it must be noted, is distinct from the state operating with a balanced budget or even having a surplus of money. In the case of balancing the budget, the goal is to ensure that all expenditures are covered by the income of the state. While aiming at a surplus might seem to be the same as aiming for a profit, the difference lies in the intent. The usual goal of achieving a budget surplus is analogous to the goal of an individual trying to save money for future expenses.

In the case of profit, the goal would be for the state to make money beyond what is needed for current and future expenses. As with all profit making, this would require creating that profit gap between the cost of the good or service and what the customer pays for it. This could be done by underpaying those providing the goods and services or overcharging those receiving them—both of which might seem morally problematic for a government.

Profit, by its nature, is supposed to go to someone. For example, the owner of a small business gets the profits. As another example, the shareholders in a corporation get some of the profits. In the case of the government, there is the question of who should get the profit. One possibility is that all the citizens get a share of the profits—although this would just be re-paying citizens what they were either overcharged or underpaid. An alternative is to allow people to buy additional shares in the federal government, thus running it like a publicly traded corporation. China and Russia would presumably want to buy some of these stocks.

One argument for the profit approach is that it motivates people; so perhaps some of the profits of the state could go to government officials. The rather obvious concern here is that this would be a great motivator for corruption and abuse. For example, imagine if courts aimed to operate at a profit for the judges and prosecutors. It could be contended that the market will work it out, just like it does in the private sector. The easy and obvious counter to this is that the private sector is well known for its corruption.

A second argument for the profit option is that it leads to greater efficiency. After all, every reduction in the cost of providing goods and services means more profits. While greater efficiency would certainly be desirable, there is the concern that costs would be reduced in ways that are harmful. For example, government employees might be underpaid. As another example, corners might be cut on quality and safety. It can be countered that the current system is also problematic since there is no financial incentive to be efficient. The easy reply to this is that there are other incentives to be efficient. One of these is limited resources—people must be efficient to get their jobs done using what they have been provided with. Another is professionalism.

In light of the above discussion, while the state should certainly aim at being efficient, it should not be regarded as a business.

The State & Business

The American anarchist Henry David Thoreau presents what has become a popular conservative view of the effect of government upon business: “Yet this government never of itself furthered any enterprise, but by the alacrity with which it got out of its way…Trade and commerce, if they were not made of India-rubber, would never manage to bounce over obstacles which legislators are continually putting in their way…”

While this sort of laissez faire view of the role of the state in business is often taken as gospel, there is the question of whether Thoreau is right. While I do find his anarchism appealing, there are some problems with his view.

Thoreau is quite right that the government can be employed to thwart and impede enterprises—this is often done by granting special advantages and subsidies to certain companies or industries, thus impeding their competitors. However, he is mistaken in his claim that the government has never “furthered any enterprise.” I will begin with the easy and obvious reply to this claim.

Modern business could not exist without the physical and social infrastructure provided by the state. In terms of the physical infrastructure, businesses need the transportation infrastructure provided by the state. The most obvious aspect of this infrastructure is the system of roads that is paid for by the citizens and maintained by the government (that is, the citizens acting collectively). Without such roads, most businesses could not operate—products could not be moved effectively and customers would be hard pressed to reach the businesses.

Perhaps even more critical than the physical infrastructure is the social infrastructure that is created by the government (that is, the people acting collectively and through officials). The social infrastructure includes the legal system, laws, police services, military services, diplomatic services and so on for the structures that compose the governmental aspects of society.

For example, companies in the intellectual property business (which ranges from those dealing in the arts to pharmaceutical companies) require the existence of the legal system and law enforcement. After all, if the state did not enforce the drug patents, the business model of the major pharmaceutical companies would be destroyed.

As another example, companies that do business internationally require the government’s military and diplomatic services to enable their business activities. In some cases, this involves the explicit use of the military in the service of business. In other cases, it is the gentler hand of diplomacy that advances American business around the world.

All businesses rely on the currency system made possible by the state and they are all protected by the police. While there are non-state currencies (such as bitcoin) and companies can hire mercenaries; these options are generally not viable for most businesses. All of this seems to clearly show that the state plays a critical role in allowing business to exist. This can, however, be countered.

It could be argued that while the state is necessary for business (after all, there is little in the way of business in the state of nature), it does nothing else beyond that and should just get out of the way to avoid impeding business. To use an analogy, someone must build the stadium for the football game, but they need to get out of the way when it is time for the players to play. The obvious reply to this is to show how the state has played a very positive role in the development of business.

The United States has made a practice of subsidizing and supporting what have been regarded as key businesses. In the 1800s, the railroads were developed with the assistance of the state. The development of the oil industry depended on the state, as did the development of modern agriculture. It could, of course, be objected that this subsidizing and support are bad things—but they are certainly not bad for the businesses that benefit.

Another area where the state has helped advance business is in funding and engaging in research. This is often research that would be too expensive for private industry and research that requires a long time to yield benefits. One example of this is the development of space technology that made everything involving satellites possible. Another example is the development of the internet—which is the nervous system of the modern economy. The BBC’s “50 Things that Made the Modern Economy” does an excellent analysis of the role of governments in developing the technology that made the iPhone possible (and all smart phones).

One reason the United States has been so successful in the modern economy has been the past commitment of public money to basic research. While not all research leads to successful commercial applications (such as computers), the ability of the collective (us acting as the state) to support long term and expensive research has been critical to the advancement of technology and civilization.

This is not to take away from private sector research, but much of it is built upon public sector foundations. As would be expected, private sector research now tends to focus on short term profits rather than long term research. Unfortunately, this view has infected the public sector as well—as public money for research is reduced, public institutions seek private money and this money often comes with strings and the risk of corruption. For example, “research” might be funded to “prove” that a product is safe or effective. While this does yield short term gains, it will lead to a long-term disaster.

The state also helps further enterprise through laws regulating business. While this might seem like a paradox, it is easily shown by using an analogy to the role of the state in regulating the behavior of citizens.

Allowing business to operate with no regulation would be like allowing individuals to operate without regulations. While this might seem appealing, for an individual to further their life, they need protections from others who might threaten their life, liberty and property. To this end, laws are created and enforced to protect people. The same applies to protecting businesses from other businesses (and businesses from people and people from businesses). This is, of course, the stock argument for having government rather than the unregulated state of nature. As Hobbes noted, a lack of government can become a war of all against all and this ends badly for everyone. The freer the market gets, the closer it gets to this state of nature—a point well worth remembering.

It might be assumed that I foolishly think that all government involvement in business is good and that all regulation is desirable. This is not the case. Governments can wreck their own economies through corruption, bad regulations and other failures. Regulations are like any law—they can be good or bad, depending on what they achieve. Some regulations, such as those that encourage fair competition in business, are good. Others, such as those that grant certain companies unfair legal and financial advantages (you might be thinking of Monsanto here), are not.

While rhetorical bumper stickers about government, business and regulation are appealing in a simplistic way, the reality of the situation requires more thought and due consideration of the positive role the state can play—with due vigilance against the harms that it can do.

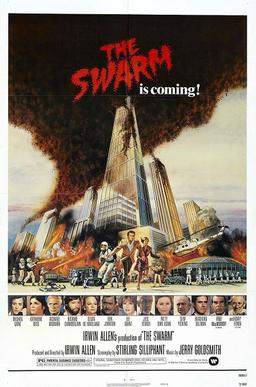

Swarms

Anyone who has played RTS games such as Blizzard’s Starcraft knows the basics of swarm warfare: you build a vast swarm of cheap units and hurl them against the enemy’s smaller force of more expensive units. The plan is that although the swarm will be decimated, the enemy will be exterminated. The same tactic was the basis of the classic tabletop game Ogre—it pitted a lone intelligent super tank against a large force of human infantry and armor. And, of course, the real world features numerous examples of swarm warfare—some successful for those using the swarm tactic (ants taking out a larger foe), some disastrous (massed infantry attacks on machineguns).

The latest approach to swarm tactics is to build a swarm of drones and deploy them against the enemy. While such drones will tend to be airborne units, they could also be ground or sea machines. In terms of their attacks, there are many options. The drones could be large enough to be equipped with weapons, such as small caliber guns, that would allow them to engage and return to reload for future battles. Some might be equipped with melee weapons, poisons, or biological weapons. The drones could also be suicide machines—small missiles intended to damage the enemy by destroying themselves.

While the development of military drone swarms will no doubt fall within the usual high cost of developing new weapon technology, the drones themselves can be relatively cheap. After all, they will tend to be much smaller and simpler than existing weapons such as aircraft, ships and ground vehicles. The main cost will most likely be in developing the software to make the drones operate effectively in a swarm; but after that it will be just a matter of mass producing the hardware.

If effective software and cost-effective hardware can be developed, one of the main advantages of the battle swarm will be its low cost. While such low-cost warfare might be problematic for defense contractors who have grown accustomed to massive contracts for big ticket items, it would certainly be appealing to those who are concerned about costs and reducing government spending. After all, if low cost drones could replace expensive units, defenses expenses could be significantly reduced. The savings could be used for other programs or allow for tax cuts. Or perhaps they will just build billions of dollars of drones.

Low cost units, if effective, can also confer a significant attrition advantage. If, for example, thousands of dollars of drones can take down millions of dollars of aircraft, then the side with the drones stands a decent chance of winning. If hundreds of dollars of drones can take down millions of dollars of aircraft, then the situation is even better for the side with the drones.

The low cost does raise some concerns, though. Once the drone controlling software makes its way out into the world (via the inevitable hack, theft, or sale), then everyone will be using swarms. This will recreate the IED and suicide bomber situation, only at an exponential increase. Instead of IEDs in the road, they will be flying around cities, looking for targets. Instead of a few suicide bombers with vests, there will be swarms of drones loaded with explosives. Since Uber comparisons are now mandatory, the swarm will be the Uber of death.

This does raise moral concerns about the development of the drone software and technology; but the easy and obvious reply is that there is nothing new about this situation: every weapon ever developed eventually makes the rounds. As such, the usual ethics of weapon development applies here, with due emphasis on the possibility of providing another cheap and effective way to destroy and kill.

One short term advantage of the first swarms is that they will be facing weapons designed primarily to engage small numbers of high value targets. For example, air defense systems now consist mainly of expensive missiles designed to destroy very expensive aircraft. Firing a standard anti-aircraft missile into a swarm will destroy some of the drones (assuming the missile detonates), but enough of the swarm will probably survive the attack for it to remain effective. It is also likely that the weapons used to defend against the drones will cost far more than the drones, which ties back into the cost advantage.

This advantage of the drones would be quickly lost if effective anti-swarm weapons are developed. Not surprisingly, gamers have already worked out effective responses to swarms. In D&D/Pathfinder players generally loath swarms for the same reason that ill-prepared militaries will loath drone swarms: while the individual swarm members are easy to kill, it is all but impossible to kill enough of them with standard weapons. In the game, players respond to swarms with area of effect attacks, such as fireballs (or running away). These sorts of attacks can consume the entire swarm and either eliminate it or reduce its numbers so it is no longer a threat. While the real world has an unfortunate lack of wizards, the same basic idea will work against drone swarms: cheap weapons that do moderate damage over a large area. One likely weapon is a battery of large, automatic shotguns that would fill the sky with pellets or flechettes. Missiles could also be designed that act like claymore mines in the sky, spraying ball bearings in almost all directions. And, obviously enough, swarms will be countered by swarms.

The drones would also be subject to electronic warfare—if they are being remotely controlled, this connection could be disrupted. Autonomous drones would be far less vulnerable, but they would still need to coordinate with each other to remain a swarm and this coordination could be targeted.

The practical challenge would be to make the defenses cheap enough to make them cost effective. Then again, countries that are happy to burn money for expensive weapon systems, such as the United States, would not need to worry about the costs. In fact, defense contractors will be lobbying hard for expensive swarm and anti-swarm systems.

The swarms also inherit the existing moral concerns about non-swarm drones, be they controlled directly by humans or deployed as autonomous killing machines. The ethical problems of swarms controlled by a human operator would be the same as the ethical problems of a single drone controlled by a human, the difference in numbers would not seem to make a moral difference. For example, if drone assassination with a single drone is wrong (or right), then drone assassination with a swarm would also be wrong (or right).

Likewise, an autonomous swarm is not morally different from a single autonomous unit in terms of the ethics of the situation. For example, if deploying a single autonomous killbot is wrong (or right), then deploying an autonomous killbot swarm is wrong (or right). That said, perhaps there is a greater chance that an autonomous killbot swarm will develop a rogue hive mind and turn against us. Or perhaps not. In any case, Will Rodgers will be proven right once again: “You can’t say that civilization don’t advance, however, for in every war they kill you in a new way.”

National Concealed Carry Reciprocity

Most states in the United States require citizens to acquire a concealed carry permit to legally carry a concealed weapon, typically a pistol. Some states, such as Florida, have permits that allow citizens to carry a range of weapons, while other states limit concealed carry to handguns. Some states allow citizens to conceal carry without a permit. While there are some similarities between the state requirements for a concealed carry permit, they do vary. For example, Florida requires applicants to undergo fingerprinting for a background check. Maine, in contrast, does not (or did not, the last time I got my permit). As it now stands, states do not always accept permits from other states. For example, Maine does not have reciprocity with Florida. However, many states do accept permits from other states, although this can change quickly.

Because not all states have reciprocity, the NRA has been backing legislation that would mandate concealed carry permit reciprocity across all the states. Laying aside the stock appeals to the Second Amendment, there are a variety of arguments that can be advanced in favor of this legislation.

One of the standard approaches is an argument from analogy comparing the driver’s license to the concealed carry permit. The gist of the reasoning is that just as states do (and should) accept drivers’ licenses from all other states, they should do the same for concealed carry permits. The analogy can be unpacked into more specific reasons.

It is contended that having reciprocity would create a consistent system in which a person licensed to carry in one state would be licensed to carry in another state and they would not need to worry about having to check to see if such reciprocity existed. A person who needed to carry in multiple states would also not need to go through the hassle and expense of getting multiple permits. Currently, when states lack reciprocity a person needs to do just that and the permit process can involve considerable paperwork and the cost can approach or even exceed $100. I had to go through this process to get a permit for my adopted state of Florida and my home state of Maine. As such, I find the convenience, consistency and cost savings based arguments appealing. There are, however, some reasonable arguments against such reciprocity.

One stock concern is that the reciprocity law would set the requirements for concealed carry permits to the weakest requirements in the United States. In general, states do allow non-residents to acquire permits, so a person in a strict state could bypass those strict requirements by getting a permit from the most permissive state. The strict state would then be required to honor the permit.

One easy counter for this would be to do away with non-resident permits and thus require people to follow the rules of their state (this would make permits analogous to driver’s licenses). Because states would have reciprocity, there would be no reason to have non-resident permits anymore—they would be rendered pointless by the law. Except, of course, as a means of bypassing the requirements of specific states.

The elimination of non-resident permits would not be without problems. One concern is the matter of fairness. Suppose that New York had very strict requirements and Texas had very loose requirements. While New Yorkers would not be able to bypass the requirements by getting non-resident permits from Texas, Texans could come to New York and carry using their Texas permits.

A counter to this would be to require that all states have comparable requirements. The obvious problem with this is that it leads back to the original concern about the state with the weakest requirements setting the standard for all states. This could be addressed by developing a uniform national standard that all states accept. This would presumably increase the requirements for some states and weaken them for others, but this would be a matter of practical politics and could be worked out.

A second concern is based on stock conservative arguments about state rights and local control. As it now stands, states have the right to set their own permit requirements and to decide which states they will grant reciprocity to. The reciprocity law would rob the states of this power and take away local control, presumably replacing it with rules imposed by the federal government.

This imposition on the state could be ideologically problematic. Gun right folks tend to also profess a commitment to states’ rights and local control while expressing a dislike and distrust of federal power. One way to get around this problem is to note that gun rights folks are fine with the Second Amendment and this is a national law. This could provide the basis for a principled rejection of state and local rights in favor of imposing a national concealed carry reciprocity law. Of course, the principle used to justify this could also be used to justify other laws that many gun rights folks might not like. But, that is a common problem with principles: following principles means that one does not always get what one likes.

Another way around the problem is to take the usual approach: people want what they want and consistency is irrelevant. Principles are just rhetorical points to be used or ignored as needed to get what one wants. People who like what is being done tend to forget such inconsistencies and easily lay aside principles until they match up with what they want. Then they pull these principles from the trash and insist on their absolute importance. As such, there is usually little practical cost for such an approach. And who really worries about ethics?

From a purely selfish and practical standpoint, I am fine with having such reciprocity. If it becomes law, I will only need to renew one permit, thus saving me money and time. However, I can look beyond my own selfish interests and recognize that there are legitimate concerns about such a law. From an abstract standpoint, my main concern is the imposition on state’s rights and local control. From a more practical standpoint, I am concerned about potentially harmful unintended consequences.

Fake News V: Fake vs Real

One of the challenges in combatting fake news is developing a principled distinction between fake and real news. One reason for this is providing a defense against the misuse of the term “fake news” to attack news on ideological or other irrelevant grounds. I make no pretense of being able to present a necessary and sufficient definition of fake news, but I will endeavor to make a rough sketch of how the real should be distinguished from the fake. My approach is built around three attributes: intention, factuality, and methodology. I will consider each in turn.

While determining a person’s intent can be challenging, intent does serve to differentiate fake news from real news. An obvious comparison here is to lying in general—a lie is not simply making an untrue claim, but making such a claim with an intent (typically malicious) to deceive. There are, of course, benign deceits—such as those of the arts.

There are some forms of fake news, namely those aimed at being humorous, that are benign in intent. The Onion, for example, aims to entertain as does Duffel Blog and Andy Borowitz. Being comedic in nature, they fall under the protective umbrella of art: they say untrue things to make people laugh. Though they are technically fake news, they are benign in their fakery and hence should not be treated as malicious fake news.

Other fake news operators, such as those behind the stories about Comet Ping Pong Pizza, seem to have different intentions. Some claim they created fake news with a benign intent—they wanted people to become more critical of the news. Assuming this was the intent, it did not seem to work out as they hoped. To their credit, they wanted to fail in their deceit—but this is as morally problematic as having a trusted figure lie to people about important things to try to teach them to be skeptical. As such, this sort of fake news is to be condemned.

Some also operate fake news to make a profit. Since news agencies also intend to make a profit, this does not differentiate the fake from the real. However, those engaged in real news do not intend to deceive to profit, whereas the fake news operators use deceit as a tool in their money-making endeavors. This is certainly something to be condemned.

Others engage in fake news for ideological reasons or to achieve political goals; their intent is to advance their agenda with intentional deceits. The classic defense of this approach is utilitarian: the good done by the lies outweighs their harm (for the morally relevant beings). While truly noble lies could be morally justified, the usual lies of fake news seem to not aim at the general good, but the advancement of a specific agenda that is likely to create more harm than good. Since this matter is so complicated, it is fortunate that the matter of fake news is much simpler: deceit presented as real news is fake news; even if the action could be justified on utilitarian grounds.

In the case of real news, the intent is to present claims that are believed to be true. This might be with the goal of profit, but it is the intent to provide truth that makes the difference. Naturally, working out intent can be challenging—but there is a fact of the matter as to why people do what they do. Real news might also be presented with the desire to advance an agenda, but if the intent is also to provide truth, then the news would remain real.

In regards to factuality, an important difference between fake and real news is that the real news endeavors to offer facts and the fake news does not. A fact is a claim that has been established as true (to the requisite degree) and this is a matter of methodology, which will be discussed below.

Factual claims are claims that are objective. This means that they are true or false regardless of how people think, feel or believe about them. For example, the claim that the universe contains dark matter is a factual claim. Factual claims can at least in theory, be verified or disproven. In contrast, non-factual claims are not objective and cannot be verified or disproven. As such, there can be no “fake” non-factual claims.

It might be tempting to protect the expression of values (moral, political, aesthetic and so on) in the news from accusations of being fake news by arguing that they are non-factual claims and thus cannot be fake news. The problem is that while many uncritically believe value judgments are not objective, this is actually a matter of considerable dispute. To assume that value claims are not factual claims would be to beg the question. But, to assume they are would also beg the question. Since I cannot hope to solve this problem, I will instead endeavor to sketch a practical guide to the difference.

In terms of non-value factual claims of the sort that appear in the news, there are established methods for testing them. As such, the way to distinguish the fake from the real is by consideration of the methodology used (and applying the relevant method).

In the case of value claims, such as the claim that reducing the size of government is the morally right thing to do, there are not such established methods to determine the truth (and there might be no truth in this context). As such, while such claims and any arguments supporting them can be criticized, they should not be regarded as news as such. Thus, they could not be fake news.

As a final point, it is also worth considering the matter of legitimate controversy. There are some factual matters that are legitimately in dispute. While not all the claims can be right (and all could be wrong), this does not entail that the claims are fake news. Because of this, to brand one side or the other as being fake news simple because one disagrees with that side would be unjustified. For example, whether imposing a specific tariff would help the economy is a factual matter, but one that could be honestly debated. I now turn to methodology.

It might be wondered why the difference between fake and real news is not presented entirely in terms of one making fake claims and the other making true claims. The reason for this is that a real news could turn out to be untrue and fake news could turn out to be correct. In terms of real news errors, reporters do make mistakes, sources are not always accurate, and so on. By pure chance, a fake news story could get the facts right, but it would not be thus real news. The critical difference between fake and real news is thus the methodology. This can be supported by drawing an analogy to science.

What differentiates real science from fake science is not that one gets it right and the other gets it wrong. Rather, it is a matter of methodology. This can be illustrated by using the dispute over dark matter in physics. If it turns out that dark matter does not exist, this would not show that the scientists were doing fake science. It would just show that they were wrong. Suppose that instead of dark matter, what is really going on is that normal matter in a parallel universe is interacting with our universe. Since I just made this up, I would not be doing real science just because my imagination happened to get it right.

Another analogy can be made to math. As any math teacher will tell you, it is not a matter of just getting the right answer, it is a matter of getting the right answer the right way. Hence the eternal requirement of showing one’s work. A person could simply guess at the answer at the problem and get it right; but they are not doing real math because they are not even doing math. Naturally, a person can be doing real math and still get the answer wrong.

Assuming these analogies hold, real news is a matter of methodology—a methodology that might fail. Many of the methods of real news are, not surprisingly, similar to the methods of critical thinking in philosophy. For example, there is the proper use of the argument from authority as the basis for claims. As another example, there are the methods of assessing unsupported claims against one’s own observations, one’s background information and against credible claims.

The real news uses this methodology and evidence of it is present in the news, such as identified sources, verifiable data, and so on. While a fake news story can also contain fakery about methodology, this is a key matter of distinction. Because of this, news that is based on the proper methodology would be real news, even if some might disagree with its content.

leave a comment